There is currently an estimated 48 different species (S.Lourie, unpub. data) of seahorses, genus hippocampus of the family Syngnathidae, although classification continues to be problematic. They are found in a wide range of habitats including tropical coral reefs, mangroves, seagrass meadows and even estuaries and deep water habitats. The highest diversity of seahorse are found in coastal areas in the Indo-Pacific, with up to 18 different species being recorded, (Lou rie et al., 2004).

rie et al., 2004).

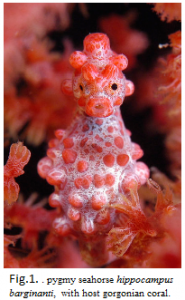

Seahorses are very unique in their physiology and anatomy, with hippocampus referring to “horse, sea monster”, they have a head that resembles a horse, an armour plated body, binocular vision and a prehensile tail. A reduction of caudal and pelvic fins results in the seahorse being a weak swimmer, it’s prehensile tail is therefore used as anchorage in strong tides. Camouflage is the seahorses best defence against predation, often perfectly blending in with their surroundings. Some species of seahorse can suddenly change colour, while others have adapted fleshy appendages to break up their silhouette and to resemble pieces of seaweed or coral in which they live amongst, others will even allow organisms to settle on them for a more natural look.

Seahorses have very unusual breeding habits, some species will pair and mate with only one another throughout the breeding season, where other species display high fidelity rates (Kvarnemo et al., 2000). The most surprising thing about seahorse reproduction is that the males are responsible for raising the young, the female has very little to do with parental care. The male has a brooding pouch in which the female inserts her oviduct and releases the eggs. The eggs are fertilised inside the brooding pouch, (Graham, 1939) where they remain for several weeks, depending on species and water temperature, before hatching and giving birth.

There are several factors that are affecting seahorse populations all over the world. The most detrimental to populations are the use of seahorses in traditional Chinese medicine, as they are believed to have healing qualities and are used to treat a variety of ailments ranging from kidney problems, impotence, broken bones, to redeem circulatory issues and even as an aphrodisiac. The seahorses are dried, mixed with other ingredients and often turned into capsule or pill form. It is believed that 95% (Vincent et al., 2011) of seahorses in trade are used in traditional medicine making this a lucrative trade with dried seahorse fetching up to a retail price of US$1,200 per kilogram in China. The extensive use of seahorses in traditional Chinese medicine and the capture of wild animals has a major impact on populations, it is estimated a 24 million seahorses were traded in 2004 amongst 77 countries, according to Project Seahorse updated.

As of 15th May 2004, all species of seahorse were added to the CITES, (Convention of the International Trade of Endangered Species), Appendix II. This does not completely define that all seahorses are threatened with extinction, but certain species may become and already are in danger if strict regulations are not soon put into place to protect wild populations. Japan, Norway, Indonesia and South Korea opted out of the CITES, and unfortunately this is where largest quantities of seahorses are landed. The IUCN, (International Union for Conservation of Nature) Red List of Threatened Species (Appendix I; www.iucnredlist.org), now holds many species of seahorse as critically endangered.

Extensive research by A. Vincent, of Project Seahorse, has shown that seahorses around the Americas are often caught in nets by mistake, particularly when trolling for live shrimp as bate. Vincent has estimated up to at least 112,000 seahorses were landed in Florida alone in 1994.

Dried seahorses that do not result in being used in medicine are often sold to tourists as souvenirs, this is known as curios trade, (Grey et al., 2005) estimated a 65,000 individual seahorses were imported into the USA in a single year.

Habitat loss and destruction is another huge threat to the seahorse, with much talk about climate change, questions regarding the overall health of the oceans are being asked, this would not only affect the seahorse in particular, but every other organism that relies on the ocean for survival. Humans encroaching on seahorse habitat is also another factor that could put seahorses at risk. Increased tourism, such as diving, as well a larger number of ports and docks, with busier shipping routes, water and noise pollution, along with the introduction of non native species, are all factors that can put seahorses and their environments under greater pressures, (Jackson et al., 2001).

Seahorses are also very sought after in the aquarium trade by private aquariums and hobbyists although considerably less when compared to the numbers used in traditional medicine. Due to the specific needs of many seahorses, they usually do not fare very well in captivity and most end up starving, their natural habitat can be hard to recreate in an artificial setting, the main issue is ensuring that enough live food is present to sustain the seahorses for the duration of its lifetime.

Due to the delicate nature of the seahorse, such as reduced mobility, particular habitat requirements and very specific breeding and fry rearing behaviours, makes seahorses exceptionally vulnerable. Studies have only recently been undertaken to try and understand seahorses, to determine the health of the populations and what we can do to conserve them. Captive breeding seahorses for certain trades, such as for aquarium, will help reduce pressure of wild caught specimens, but improvement is needed to increase the success rate of the captive bred for it to have any effect.

Researchers are now working closely with fisheries and other organisations to help calculate, protect and maintain sufficient seahorse populations. Encouraging alternative fishing methods to reduce accidental catch, at specific areas at certain times, i.e. outside breeding seasons, as well as introducing size minimums on captured specimens and introducing marine protected areas (MPAs), will all help improve the chances of the seahorse. Unfortunately, there is still much to learn about the seahorse and it’s way of life, until only recently was it realised how threatened they actually are and much more work will need to be done to help secure a future for these amazing animals, hopefully it is not too late.

References

Amanda Vincent et al., (2004) – Underwater Visual Census for Seahorse Population Assessments.

Kvarnemo et al. (2000) -Monogamous pair bonds and mate switching in the Western Australian seahorse Hippocampus subelongatus.

Vincent et al., (2011)– Conservation and management of seahorses and other Syngnathidae.

Hall Heather J., Lourie Sara A., & Vincent Amanda C.J. (1999). – Seahorses: An Identification Guide to the World’s Species and Their Conservation.

Jackson et al., (2001) – Water in a Changing World.

Grey et al., (2005) – Magnitude and trends of marine fish curio imports to the USA.

Lourie et al.,(2004) – A guide to the identification of seahorses.

http://www.iucnredlist.org/search

http://www.cites.org/common/com/AC/20/E20i-24R.pdf

Fig 1. –http://www.npr.org/blogs/pictureshow/2011/04/05/135143934/the-creative-evolution-of-sea-creatures by Jonathan Makiri, April 05, 2012.

Fig 2. – Zoo News Digest 1st – 4th August 2012 (Zoo News 826).