As humans, it seems as though the fear of sharks, along with other elasmobranchs, is hardwired into our brains. The mere image of a dark, triangular dorsal fin penetrating the surface of the water or a stingrays sharp caudal barb getting a little too close for comfort while swimming in a tropical lagoon may send shivers down our spine.

Much like our methods of interacting with other wild animals, we should aim to respect sharks and rays when we encounter them to avoid putting both parties in danger. With attacks being a rare instance, how can we alleviate some of the fear associated with cartilaginous fishes? The answer may lie in the knowledge of planktivorous sharks which, despite being large, are harmless to humans.

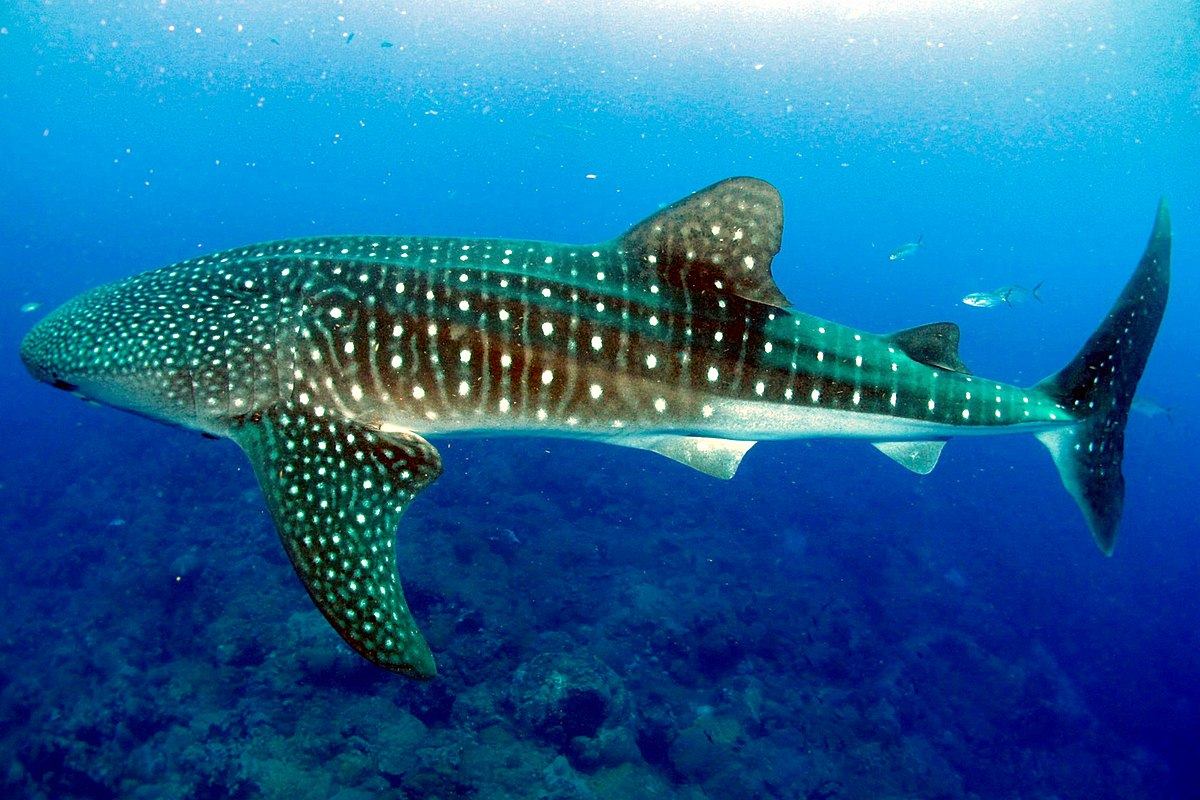

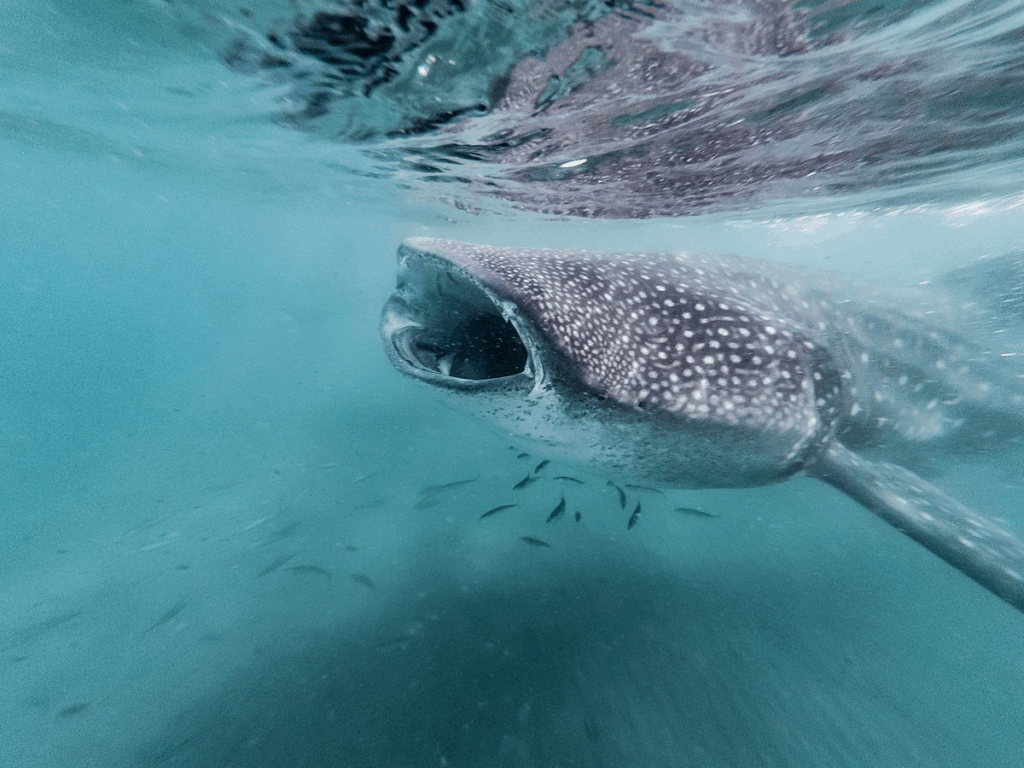

There are currently three known planktivorous sharks alive today: the whale shark (Rhincodon typus), the basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus), and the megamouth shark (Megachasma pelagios). These three sharks are not closely related, given that they are in monospecific families, or biological families that only contain one living species. Despite taxonomical differences, each of these species share a significant characteristic: their diets consisting primarily of zooplankton and small fishes. Minute hooked teeth, large size, slow movement, and large oral cavities are also observed between these unique cartilaginous fishes.

Out of the three species, the megamouth shark is the least understood by scientists, with fewer than 300 individuals documented. Behavior of planktivorous sharks, like other animals, is highly dependent on tagging, which uses satellites to provide information on their horizontal movement patterns. Data on vertical movement is trickier to obtain, but based on both detections from tags and their unique diet, it is clear that these sharks exhibit behaviors of diel vertical migration.

Due to their large size compared to how small their prey is, it is believed that these sharks are practically always feeding. With that being said, it is crucial for each of these species to follow their food. Basking sharks and whale sharks tend to spend the daytime grazing at the surface where primary productivity is high. When it is night and light levels are low, they return to deeper waters to avoid predation, regulate their body temperature, and continue feeding. In contrast, megamouth sharks have been known to spend most of the day in deeper waters where they feed on zooplankton, surfacing only at night.

Planktivorous sharks have developed different strategies to ensure that they are taking in enough food, while also behaving in ways that best suits their bodies and metabolism given the environments that they inhabit. Their size and feeding mechanism, that is, drifting through the water with their large mouths open, may come off as terrifying for some. It is important to remember that we, as humans, are more likely to put these marine megafauna at risk than they are to harm us. Ship strikes are sadly common in our oceans due to our growing demand for resources as our population expands. These collisions are often fatal for large filter-feeding animals, and we unintentionally attract them towards ship routes through man-made structures such as oil and gas platforms, which provide hard habitats close to the surface for sessile organisms and often accumulate high biodiversity. As a result, filter-feeders often congregate near these artificially-made environments in order to maximize their food consumption, which frequently exposes them to large vessels.

It can be difficult to transition out of the mindset that the ocean and its inhabitants are frightening, but being able to understand how harmless these creatures are can motivate us to advocate for them and their homes. In our rapidly changing world, protecting ecosystems has become vital and it is our responsibility to minimize the damage we have caused.

Featured image courtesy of the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, taken at the Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary.