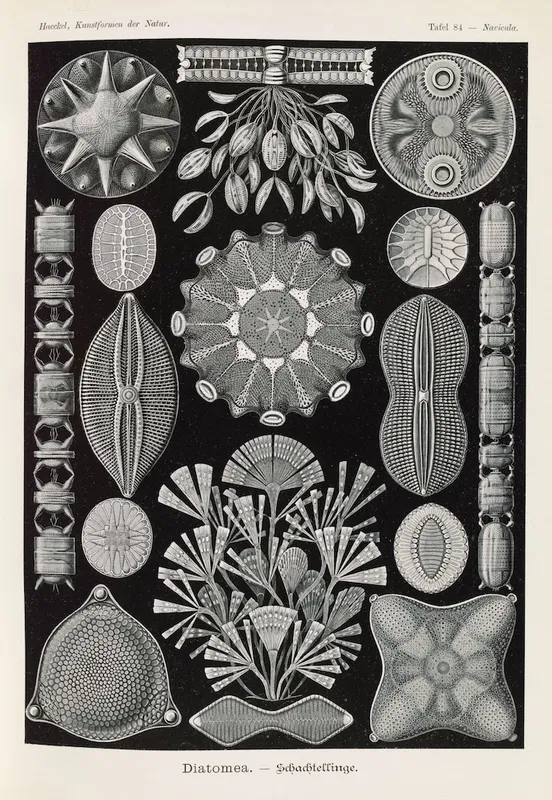

Diatoms are all around us. They are just one type of phytoplankton in our oceans, marine photosynthetic microorganisms that drive many of Earth’s unseen processes. Diatoms have a staggering amount of diversity, with over 200 genera and roughly 110,000 morphologically distinct species. They make up a large proportion of seafloors, the dirt under our feet, rivers, and seawater (1). These hardy organisms are found in nearly every marine environment and many terrestrial ones on Earth. They are well known for their incredible morphological and ecological diversity, but they all share one very important characteristic: their porous silica frustule.

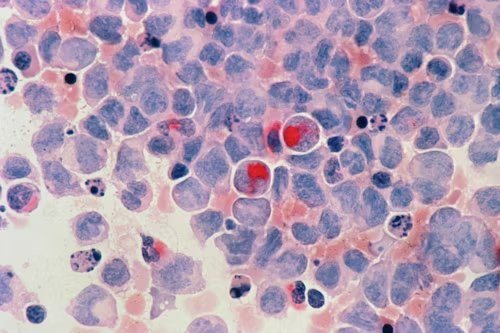

Diatoms could be a crucial next step in cancer research, drug development and delivery. A major challenge in cancer treatment is targeting cancer-affected cells with an apoptosis-causing drug while sparing surrounding noncancerous cells. Radiation therapy, for example, essentially blasts the affected area and nearby tissue in order to prevent metastasis. There has been some success with synthetic nanoparticle drug delivery systems; however, these nanoparticles are costly and time-consuming to produce, making large-scale, viable treatments difficult.

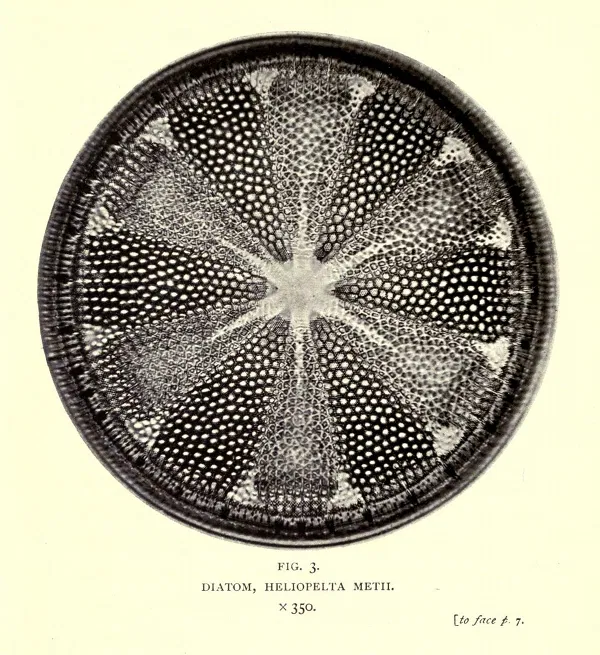

Utilizing diatoms, as it turns out, could provide an eco-friendly and cost-effective source of nano-porous silica. They are composed of a highly organized, porous silica shell called a frustule. Researchers can isolate this outer silica layer and use it as a silica-based nanoparticle drug carrier, coating or loading it with a cancer treatment drug. The surface can then be chemically engineered so that overexpressed receptors on cancer cells recognize attached ligands on the nanoparticle and bind to it. While the silica particles themselves are generally biocompatible, when concentrated in cancer cells, they can deliver apoptosis-inducing drugs directly where they are needed (2). This would make cancer treatments more effective and ideally result in fewer side effects for patients.

These abundant organisms, often overlooked, could be a critical turning point in drug therapies. However, there are still challenges. Research in this area is relatively new, and the stability of the silica nanoparticles needs to be improved, as well as better control over the size and morphology of diatoms when grown in a lab. Another obstacle is the question of biodegradability, ensuring that the frustules do not accumulate in the liver and cause additional complications (3). Additionally, more research must be conducted to ensure drug loading efficiency and reliable drug release before this treatment tool can be clinically implemented on a larger scale.