Immense pressure, extreme temperatures, and resource scarcity have stimulated numerous adaptations in deep-sea fauna that allow them to withstand highly selective pressures. Organisms that live in exceptionally intense environments are referred to as extremophiles, composed mainly of microbes (primarily autotrophs, i.e., organisms that convert inorganic substances into nutrients and energy) and benthic invertebrates. Such organisms can be found at deep-sea hydrothermal vents and cold seeps—chemosynthetic ecosystems in which microbes utilize the hydrocarbons (e.g., hydrogen sulfide and methane) that are released from the Earth’s crust via fluids to generate energy in the absence of sunlight. Despite hostile conditions, communities that inhabit these ecosystems flourish because chemosynthetic organisms support upper trophic levels; autotrophic processes are reciprocally dependent on heterotrophs. For example, the ammonia produced by heterotrophs is nitrified by archaea, substantially contributing to rates of chemosynthesis (Danovaro et al., 2017). Chemosynthetic systems create thriving communities in an otherwise desolate and scarce deep-sea environment.

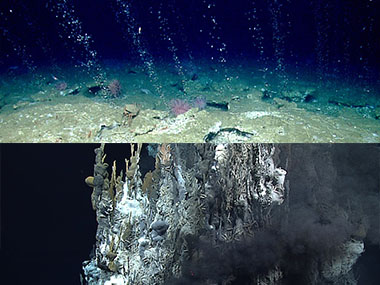

Hydrothermal vents, possibly the most well-known chemosynthetic ecosystems, are home to a diverse selection of organisms that range from the autotrophic microbes to tube worms and yeti crabs. Volcanically driven, these vents release magma-heated, mineral-rich fluid. Plumes from these vents produce about 107 times more methane than the ocean water around them, allowing for highly increased productivity and ecosystem functionality due to the microscopic organisms that oxidize and metabolize it (Zeng et al., 2021). The microbial populations that make up the basis of hydrothermal vent ecosystems are crucial to not only the success of the communities within them, but also for the biogeochemical cycles (carbon, nitrogen, etc.) that drive ocean-atmosphere processes. For instance, archaea around vents can consume around 75% of the methane released from the vents through anaerobic oxidation of methane (AOM) (Zeng et al., 2021). These microbes and their symbionts rely on superheated fluid; however, chemosynthesis is also possible in cold ecosystems.

Similar to hydrothermal vents, organisms in cold seeps also utilize fluid from the seafloor for energy. That said, cold seeps are geologically very different—they are a tectonic formation rather than volcanic, and therefore are not heated due to a lack of magma. They are ambient to the surrounding temperature of the seawater and flow slower than vents (Suess, 2014). Despite the drastic differences in temperature, the communities inhabiting cold seeps are resemblant of those inhabiting hydrothermal vents. Tube worms and bivalves such as mussels are common, and are reliant on the bacterial mats that provide energy via AOM. Deep-sea chemosynthetic communities, in both hydrothermal vents and cold seeps, are vital to biodiversity and the functionality of the ocean.