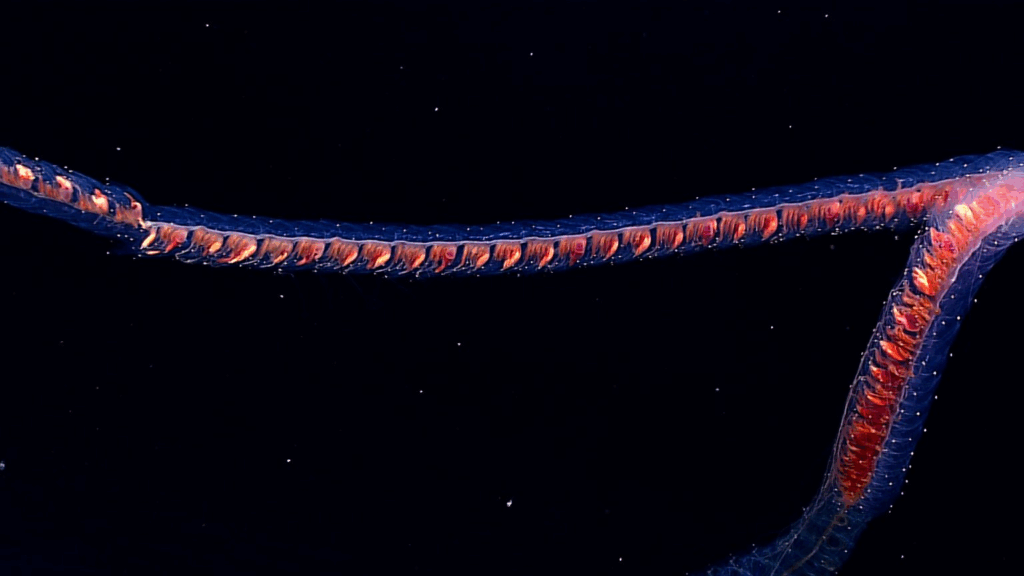

Siphonophores are large colonies of small zooids—individual animals that must live together to survive—which gives them their alien-like appearance in the deep ocean. They typically reside between 700 and 1,000 meters below the surface. Giant siphonophores are among the largest organisms in the ocean, reaching lengths of 40 meters or more, although their bodies remain relatively thin, often only as thick as a broomstick. Composed of jelly-like tissue, they often display a colorful ribbon of digestive tract running through their length. They belong to the class Cnidaria, yet are strikingly different from jellyfish or corals, even though all rely on zooids that form specialized body parts. (Monterey Bay Aquarium) Every zooid contributes a specific role, creating a perfectly coordinated colony.

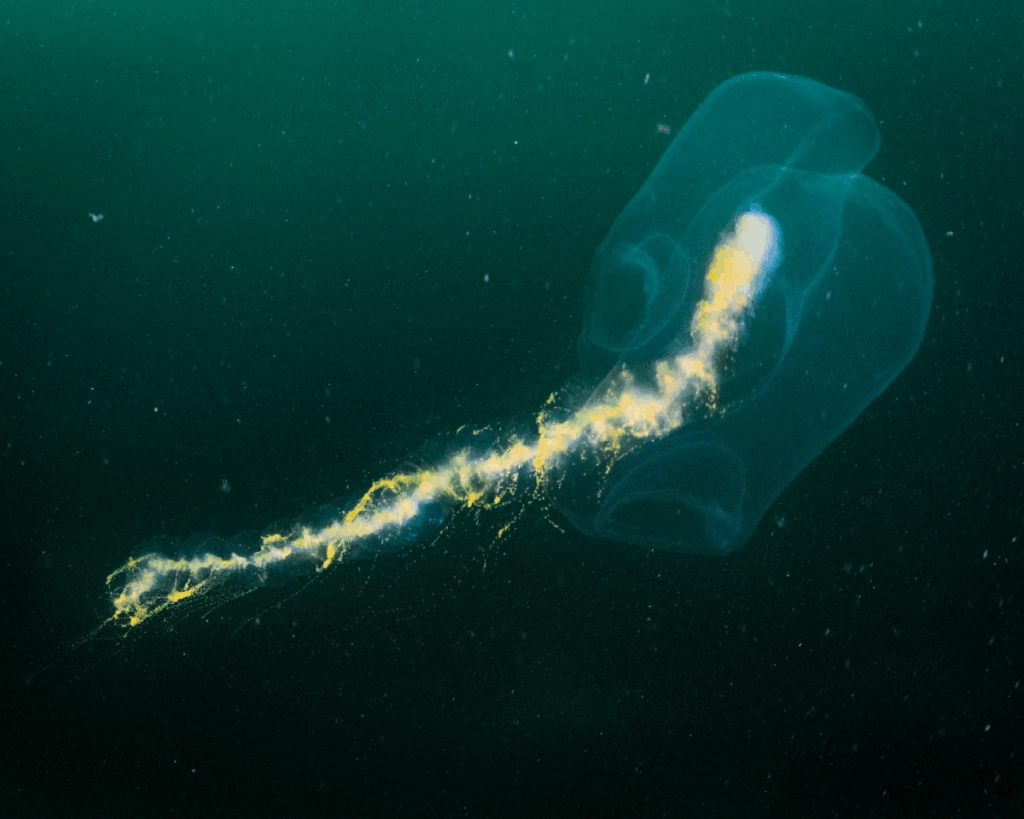

A giant siphonophore’s body is made up of hundreds of zooids that work collectively, each performing a particular job such as swimming, feeding, or reproducing. None of them can survive independently—many are actually clones of the original zooid and carry out the same function. Zooids develop from a single fertilized egg, and like corals, new ones bud off from the original, forming nearly identical copies that later specialize. These zooids are extraordinarily specialized: some digest food caught by other zooids; others propel the organism or handle reproduction. Despite functioning like parts of a single animal, the zooids themselves are technically individual creatures, all connected by shared tissue or a common exoskeleton. (Schmidt Ocean Institute) The organism as a whole is extremely fragile—minor disturbances can cause sections to break apart, leaving behind a goo-like mass.

Giant Siphonophore, NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research Image

What makes these long, delicate animals especially fascinating? They can produce red light—a rarity in the deep sea. Giant siphonophores were the first known invertebrates discovered to generate red bioluminescence. (siphonophores.org) They use this light to lure prey; the glow attracts fish, their nematocysts deliver the sting, and specialized digestive zooids process the meal. Yet giant siphonophores remain poorly studied due to the challenge of observing them. They cannot simply be netted, and their delicate, jelly-like bodies make sampling difficult. Most observations come from deep-sea dives and remotely operated vehicles.

Siphonophore, Monterey Bay Aquarium Image

Giant siphonophores are a scientific mystery—remarkable for their red-light production, their unique colonial structure, and their extraordinary size. They are among the largest creatures in the ocean, yet remain surprisingly overlooked, making them one of the sea’s most captivating unknown marvels.

Feature Image Citations

Monterey Bay Aquarium

https://www.montereybayaquarium.org/animals/animals-a-to-z/giant-siphonophore

Citations

“Giant Siphonophore.” Montereybayaquarium.org, 2020, www.montereybayaquarium.org/animals/animals-a-to-z/giant-siphonophore.

“Siphonophores.” Siphonophores.org, 2019, www.siphonophores.org/SiphLifeCycle.php.

Dunn, Casey. “Siphonophores.” Current Biology, vol. 19, no. 6, Mar. 2009, pp. R233–R234, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2009.02.009.Mackie, G.O., et al. “Siphonophore Biology.” Advances in Marine Biology, 1988, pp. 97–262, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0065-2881(08)60074-7. Accessed 1 Nov. 2020.

“Creature Report: Siphonophores.” Schmidt Ocean Institute, schmidtocean.org/cruise-log-post/creature-report-siphonophores/.