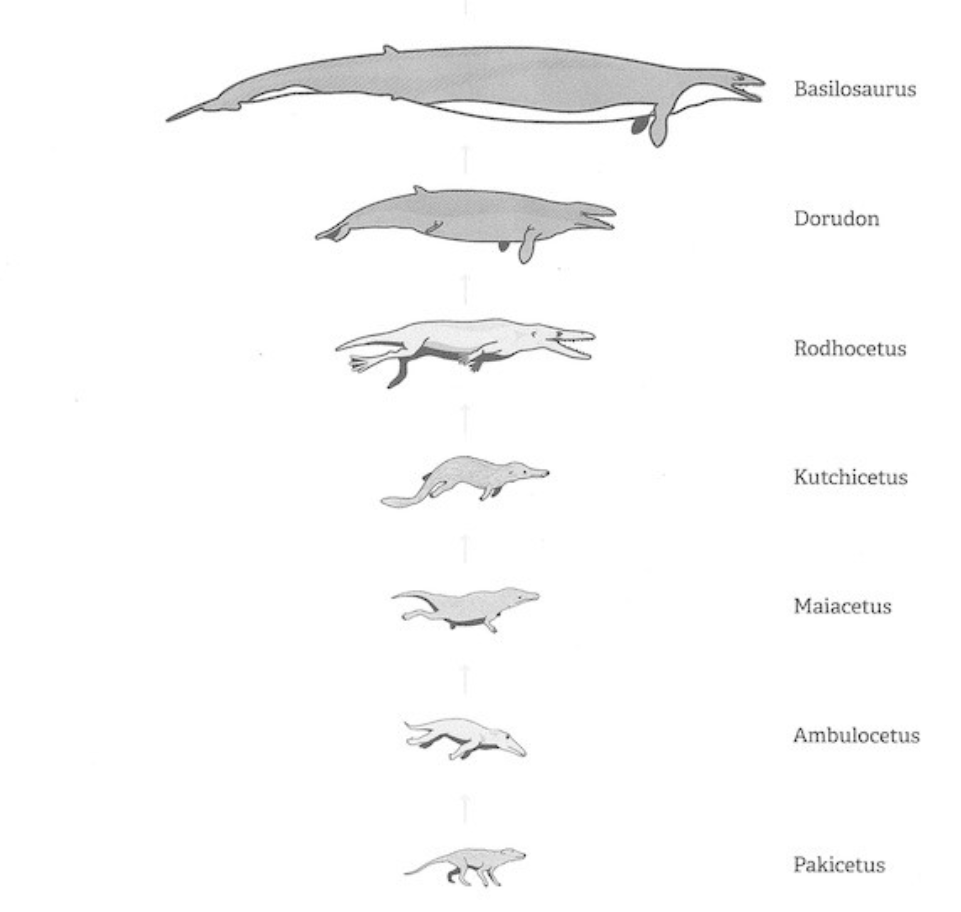

Many people don’t know marine mammals used to live on land- over 50 million years ago the bodies of land dwelling mammals transformed dramatically as they adapted to life in the water. Fossils from prehistoric animals like Pakicetus, Ambulocetus, Remingtonocetus, and Basilosaurus show clear steps in this evolution of land to ocean.

Let’s start with the first steps in the process; Pakicetus lived around 50 million years ago and looked very much like a small dog-like land mammal. It had long legs, fur, ears, and teeth well suited for hunting and eating fish ([1]de Muizon, 2009). Although it lived mostly on land, Pakicetus was able to hear underwater and had dense bones, allowing it to thrive in semi-aquatic environments, though its body was not yet adapted for swimming long periods of time- think of this similar to current day otters, or even beavers ([2]de Muizon, 2009).

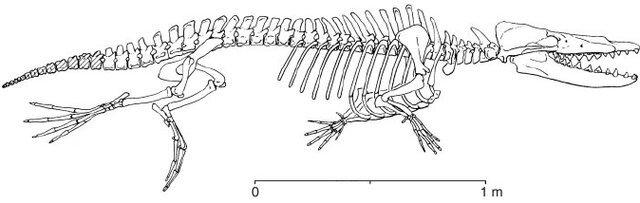

A few million years later came Ambulocetus, a semi-aquatic predator about the size of an alligator, which most call the ‘walking whale’. Ambulocetus could both walk and swim, had strong hind limbs for pulling itself along riverbanks and its spine and tail became more flexible which are traits very useful for moving through water easily ([2]de Muizon, 2009)

Skip to around 45 million years ago, Rodhocetus had a more elongated body, shorter limbs, and a stronger tail for even better propulsion underwater. The skull also grew more streamlined ([1]Boessenecker, R., n.d.) and its nostrils began to move slightly backward on the snout, which is indicative of what would later become a blowhole. The fossils found also show reduced hind limb function which is an important step toward the fully aquatic life these animals were evolving into ([3] Gingerich, Philip., et al. 2001)

Living around 35 to 40 million years ago, we find the Basilosaurus- its skeleton now resembles a fully aquatic mammal with its eel-like body, powerful tail flukes, and flipper-like forelimbs ([5] Zhang & Goodman, 2023). Its hind limbs were tiny, useless for walking, and vestigial (small remnants of the limbs its ancestors used on land). The Basilosaurus is one of the major common ancestors of modern whales before they diverged into separate lineages since baleen whales usually feed on zooplankton, while toothed whales eat a wide variety of prey ([5] Zhang & Goodman, 2023), including fish and marine mammals. These fossils are some of the clearest evolutionary clues in the fossil record to hint towards past life on land. Basilosaurus also had a more streamlined skull and a fully developed blowhole, making it look far closer to modern whales than its previous ancestors.

The evolution of Pakicetus to Basilosaurus reveals how natural selection reshaped early whales as they moved from land to water. Their limbs shrank while their skulls and bodies got more streamlined as these animals entered new habitats. What’s really interesting is how modern whales still carry traces of their land-bound ancestors with pelvic bones, vertical tail movement, and their need to surface for air.

References:

- [1] Boessenecker, R. (n.d.). Rodhocetus spp. In Evolution of Dolphins & Whales – Cetacean Family Tree. New York Institute of Technology. https://www.nyit.edu/medicine/college-of-osteopathic-medicine/anatomy/evolution-of-dolphins-and-whales/cetacean-family-tree/rodhocetus-spp/. https://www.nyit.edu/medicine/college-of-osteopathic-medicine/anatomy/evolution-of-dolphins-and-whales/cetacean-family-tree/rodhocetus-spp/ de Muizon, C. (2009). L’origine et l’histoire évolutive des Cétacés. Comptes Rendus Palevol, 8(2–3), 295–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crpv.2008.07.002

- [2] de Muizon, C. (2009). L’origine et l’histoire évolutive des Cétacés. Comptes Rendus Palevol, 8(2–3), 295–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crpv.2008.07.002

- [3] Gingerich, Philip & Haq, M.Aman Ul & Zalmout, Iyad & Khan, Intizar & Malkani, M. Sadiq. (2001). Origin of Whales from Early Artiodactyls: Hands and Feet of Eocene Protocetidae from Pakistan. Science (New York, N.Y.). 293. 2239-42. 10.1126/science.1063902.

- [4]Jonathan Wells, Zombie Science (Seattle: Discovery Institute Press, 2017), 107-112.

- [5] Zhang, P., & Goodman, S. J. (2023). Learning from the heaviest ancient whale. The Innovation, 4(5), 100501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xinn.2023.100501.