Breathing Life Back into the Ocean

There’s something incredible about stepping onto a dock and watching the surface of the water shimmer with life. Yet beneath that beauty, our oceans are changing faster than ever. Climate change and pollution are stressing marine ecosystems, altering currents, and pushing species to the brink. As a student of aquaculture and fisheries science, I’m fascinated by how human innovation can both harm and heal.

Take aquaculture, for example. When done responsibly, fish farming has the potential to provide food security, reduce pressure on wild stocks, and even help restore species in decline. Visiting hatcheries and research facilities has shown me how much detail goes into raising healthy fish — from water quality and diet to disease management. It’s a reminder that the ocean’s future may depend not just on conservation, but on building sustainable systems that work with nature rather than against it.

Net Pen Culture: Promise and Controversy

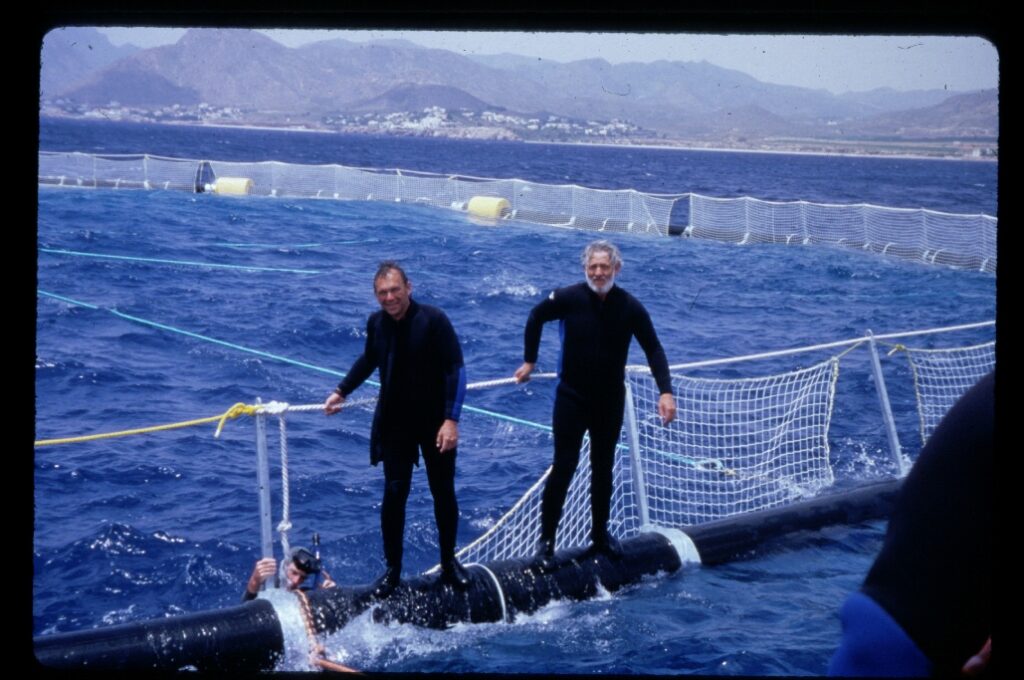

One of the most widely used aquaculture techniques is net pen culture. These are floating cages anchored in sheltered bays or coastal waters, where fish like salmon are raised in large numbers. The appeal is obvious: net pens use the ocean itself as a growing system, with natural water flow delivering oxygen and carrying away waste. They allow for high production, which helps meet the world’s growing demand for seafood.

But net pen culture is far from perfect. Waste from uneaten feed and fish excretion can build up under pens, altering habitats and fueling algae blooms. Escaped farmed fish can mix with wild populations, sometimes spreading disease or competing for resources. These challenges have led critics to label net pens as environmentally harmful.

Yet, innovation is reshaping the conversation. Farmers are experimenting with better feeds, vaccines, and monitoring technology to reduce disease and waste. Some companies are moving pens further offshore, where stronger currents dilute impacts, while others integrate pens with shellfish or seaweed farming to absorb excess nutrients. These approaches show that net pens, while controversial, could evolve into a more sustainable option when paired with science-driven management.

Why Conservation Feels Personal

For me, the ocean isn’t just an abstract idea. It’s weekends spent kayaking with family, snorkeling in quiet coves, and learning to sail small boats. Those experiences sparked a curiosity that became a career path, but they also made the stakes real. When you’ve watched a school of fish scatter below you or seen how coastal ecosystems knit together, it’s hard not to feel protective.

That’s why I see conservation as more than research or regulation — it’s about connection. Education, storytelling, and community involvement are powerful tools. Whether it’s teaching kids about pollinators in a local garden or explaining how warming waters affect lobsters, sharing knowledge builds momentum for change. If people can see themselves in the story of the ocean, they’re more likely to fight for it.