What comes to mind for most people when they think of a sea turtle might be the hard shelled, tropical animals that largely eat seagrasses and crustaceans. However, the leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea) completely strays from the normal ideation of the sea turtle. This is because of their unique physiology and diet. The leatherback has adapted to dive up to depths of 1,200 meters in search of food, enduring the steadily increasing pressure and decreasing temperature as they descend. As a result, they are significantly larger than other sea turtle species, a trait that has helped them stay structurally sound and retain body heat while hunting for jellyfish and salps.

The leatherback has evolved to have a flexible leathery carapace that allows it to compress rather than crack under extreme oceanic pressure which protects the turtle from nerve damage. They protect their vital organs by collapsing their lungs-trachea-larynx system which allows them to complete several dives in succession without taking any structural damage.

The lungs compress first as external pressure increases, reducing buoyancy and preventing nitrogen exchange. As the dive deepens, the Trachea collapses next, further minimizing gas exchange, while also entrapping air to act as a counterbalance and to resist against possible deformation. Then, the larynx closes tightly to seal the airway and protects the sea turtle’s internal system under extreme pressure.

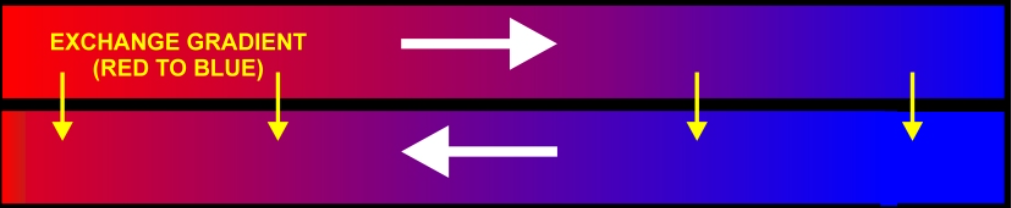

The Leatherback has also adapted a countercurrent heat exchange mechanism in order to efficiently find food without freezing to death. Countercurrent heat exchange allows for the constant circulation of heat even in cold environments found at lower depths. As blood flows out from the core arteries to external appendages, heat is held, and then lost. To prevent an extreme loss in body heat, which often results in death, veins returning blood from the flippers run alongside the arterial veins. This countercurrent exchange allows the returning venous blood to heat up before re-entering the body core.

This mechanism makes the leatherback not only the deepest diver, but also the only warm blooded sea turtle. Other sea turtle species partake in behavioral thermoregulation, which means they adjust their depth, staying in shallower water and then diving deeper to cool down.

Despite these incredible adaptations, like all turtles, the leatherback is critically endangered. Leatherbacks are often subject to boat strike on the surface, and are at a constant risk of becoming bycatch in gillnets, trawl nets, and ghost nets. During feeding, it faces added danger, since plastic bags are often mistaken for one of its main sources of prey, sea jellies.

In order to mitigate the issue of bycatch, Turtle Excluder Device (TEDS) were developed, allowing leatherback sea turtles to escape nets they enter. Despite these shortcomings, continued innovation and global cooperation are essential to ensure the survivability of these incredible marine animals.

Featured Image: An endangered leatherback sea turtle swimming at the ocean’s surface. (Image credit: NOAA)