In this essay I shall be looking at why the Great White Shark (Carcharodon carcharias) has become such a notorious predator. I will be looking at both the public’s perception of Great White Sharks and also some physical and behavioural adaptations that have led to it becoming such a remarkable hunter.

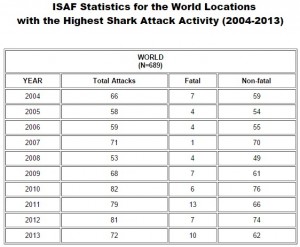

You only need to type in ‘Great White Shark’ into Google and a plethora of articles will appear about Great White Sharks attacking humans in unprovoked attacks. If you were to only take these articles into account you wouldn’t be naïve in thinking that shark attacks are an incredibly common occurrence. However the odds of you being attacked are incredibly small, you only have to look at ISAF (International Shark Attack File) to see that in 2013 there was only 72 reported attacks from sharks, with only 10 being fatal, which is an incredibly small number. (ISAF).

So if the chances of you being attacked by a Great White Shark are so low, why is an attack such a concern for holiday makers?

The main reason for this is the amount of coverage a shark attack will get. As well as being terrified of this incredible creature, the general public also has a morbid fascination with it, and love to hear about the gruesome attacks that occur. You only need to take a look at films such as Steven Spielberg’s Jaws (1975) to see that the media loves to portray Great White sharks as unpredictable and masochistic killers, when actually this couldn’t be further from the truth. In the late 1980’s a group of scientists including A. Peter Klimley carried out a series of observations on shark predation in the South Farallon Islands, 30 miles off the coast of San Diego. They looked to see how these creatures attacked and killed their prey, whether or not there were any preferences in time and location and how their technique varied depending on their prey. Klimley described the Great White Shark as ‘a skilled and stealthy predator that eats with both ritual and purpose’. During his time at the South Farallon Islands, Klimley discovered that the majority of mature Great Whites congregated near the areas where their popular prey of seals and sea lions were abundant and that the juveniles were found further down the coast, where the concentration of seals and sea lions was much less. They also discovered that predation rates peaked during the morning and slowly declined until the afternoon. They came to the conclusion that Great Whites hunted their prey in daylight hours only. This conclusion was supported by the knowledge of the high density of cone receptors found in the Great White’s retinas. Another observation was that the attacks on their prey occurred at similar times on sequential days. They believed that this was influenced by the tides, as at high tides the elephant seals which they preyed on, were forced into the water. Through a series of observations on different days they eventually found that there was a positive correlation between the frequency of attacks and the tidal height. (A. Peter Klimley, 1994). If we take into account the conclusions that Klimley and his team came to, we can clearly see that Great Whites are not opportunistic killers at all, and that they will alter their feeding times in order to maximise their chance of making a kill. From this set of observations alone we can see how much our perceptions of these creatures are altered in order to create a warped image of a deep sea monster.

So if this is the case, why are we so terrified of these creatures? Well the first thing to look at is their anatomy. The most obvious feature of these creatures is their size. The largest female shark recorded was six metres in length, making this creature one of the largest predatory fish. (Bruce et al, 2006). There are very few predatory creatures that reach this size, making it an extremely good reason to cause fear amongst those that have very little knowledge, and even those who do. Another feature that also creates this menacing image of Great Whites is their colouring. They have black tops in order to blend in with the dark sea floor beneath them. This camouflage creates a great advantage when it comes to hunting agile prey, making them incredibly difficult to be noticed by an unsuspecting seal or sea lion that may be swimming above them. However this also means that it is incredibly difficult for a diver or a swimmer to see them as well. The idea of such an impressive predator lurking beneath you would terrify anyone, especially if there is a lack of understanding about these creatures. (Patrick Counihan, 2014)

Another feature that creates a rather eerie tone to the Great White shark is the lack of a nictitating membrane. Because Great Whites lack this protective film, once they get close enough to their prey they roll their eye fully back into their socket. This is done to avoid any damage as Great Whites already have very limited vision. However when doing this the result is a rather bleak looking creature. It may seem like a very unusual thing to be scared of, but humans tend to feel emotional connections to animals, even when there aren’t any there. This emotional connection is definitely not possible with a Great White, and could be a reason as to why people think that this creature is a lot more unpredictable than it actually is.

The final physical adaptation that I will be looking at is the teeth of a Great White Shark. This is possibly one of the most prominent features of the Great White Shark, and the one that would be most daunting to humans. A Great White Shark has roughly 300 teeth, arranged into many rows. The first two rows are actually the only ones that are used for biting and killing its prey. The rows behind that are replacements, as Great White Sharks do not have fixed teeth. This is so that it does not lose an advantage when attacking its prey if one breaks off. However this creates a truly horrifying sight if you ever get the chance to look inside a Great White Shark. (Crystal Gammon, 2013)

So as we can see, the Great White Shark is a highly specialised and intelligent hunter that has an array of highly specialised adaptations, that it uses with incredible skill and precision in order to catch and kill its prey in the most efficient way possible. It is clear that the media’s portrayal of this creature is incredibly one sided, as this is not an opportunistic killer, but and incredible hunter. Not everything is perfect about this creature however, it’s poor eyesight means that it is possible for it to make mistakes, and it is this that we need to be aware of.

References

https://www.flmnh.ufl.edu/fish/sharks/statistics/statsw.htm

The Predatory Behaviour of the White Shark, A. Peter Klimley. American Scientist, Vol. 82, No.2 (March- April 1994) pp. 122-133

Bruce, B.D, Stevens, J. D, Malcolm H (2006) Movements and swimming behaviour of white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) in Australian waters. Volume 150, Number 2. pp. 69

http://www.irishcentral.com/news/Great-white-shark-1000-miles-off-Irish-coast-could-arrive-within-days.html

Anne Woods. “Unique Adaptations That Sharks Have To Survive” animals.pawnation.com <http://animals.pawnation.com/unique-adaptations-sharks-survive-7845.html>

Edmonds, Molly. “How do sharks see, smell and hear?” 29 April 2008. HowStuffWorks.com. <http://animals.howstuffworks.com/fish/sharks/shark-senses.htm> 25 October 2014.

Crystal Gammon “Fun Facts about Great White Sharks” 22 February 2013 <http://www.livescience.com/27338-great-white-sharks.html>